The

bit can be used for control, communication and collection of the

horse.

The

following excerpts are taken from bitless bridle.com to highlight how

the bit causes pain regardless of whether it is is used for control,

communication or collection.

Robert

Cook, FRCVS., PhD., Professor of Surgery

Emeritus of Tufts University, Massachusetts, is a veterinarian who,

for most of his career since graduating from the Royal Veterinary

College, London, in 1952, has been a faculty member of clinical

departments at schools of veterinary medicine in the UK and USA.

His research has

been focused on diseases of the horse's mouth, ear, nose and throat,

with a special interest in unsoundness of wind, the cause of bleeding

in racehorses, and the harmful effects of the bit method of

communication.

The horse's mouth

is one of the most sensitive parts of its anatomy. The application of

pressure to a steel rod inserted in this cavity inflicts unnecessary

pain and frightens a horse. Fear initiates a flight or fight response

(bolting or countless forms of resistance). In addition, putting a

bit in the mouth of a horse that is about to run, is akin to putting

a muzzle on a horse that is about to eat. A bit is contraindicated,

counterproductive and, in the wrong hands, potentially cruel. His

research has shown that the bit is responsible for over a hundred

behavioral problems. Cook is happy to endorse the Bitless Bridle as a

preferable alternative to the Bronze Age technology of the bit.

Excerpts taken from:

http://www.bitlessbridle.com/index.php?main_page=page&id=1#q5

The

mouth is one of the most highly sensitive parts of the horse's

anatomy.

Even

the gentlest use of a bit causes pain.

As

the horse is a prey animal it has evolved to hide its pain as much as

possible in order to avoid attracting predators. Nevertheless, signs

of bit-induced pain, as expressed by changes in behaviour, are common.

They are expressed by the four F's ? fear, flight, fight and facial

neuralgia. Dr. Cook?s research has shown that there are not less than

120 different signs of bit-induced pain.

Just as food

in the mouth stimulates digestive

system reflexes, so also does a bit. A bit signals a horse to "think eat". Yet a horse at exercise needs to "think exercise". The bit stimulates digestive system responses, whereas exercise requires respiratory, cardio-vascular and musculo-skeletal system responses. Eating and exercising are two incompatible and mutually exclusive activities. Horses have not evolved, anymore than we have, to eat and exercise simultaneously.

Diagram A: Below

Normal configuration of the throat for bitless horse

whilst running.

Note: The soft palate is 'vacuum packed' and stable in its normal position. There is an airtight seal at the lips and between the two parts of the throat allowing air to freely pass into the lungs.

Diagram B: Below

Abnormal configuration of the throat when running in a bitted bridle. The bit (yellow dot) has broken the lip seal, allowing air to enter the oral part of the throat.

The soft palate (flap) is UNSTABLE and is shown in

an elevated position that is ONLY APPROPRIATE to a phase of swallowing.

THE AIRWAY IS SEVERELY OBSTRUCTED at the junction of the nasal cavity and the throat (red dots)

For the purpose of eating, the horse responds with an open mouth, reflex salivation, and movement of the lips, tongue and jaw. All these responses are stimulated by the presence of a bit. When a bit is in place, for example, retraction of the tip of the tongue tends to occur.

If you place a pencil in your own mouth, you instinctively explore it constantly with the tip of your tongue. The horse does the same with a bit and, consequently, the root of the tongue often bulges upward and moves the soft palate in the same direction.

The throat, which is capable of serving either swallowing or deep respiration (one or the other but not both at the same time) is, by the presence a bit, programmed for swallowing. Accordingly the tongue tends to be mobile and so also is the soft palate which lies on the root of the tongue.

From time to time during exercise, the soft palate will tend to be pushed up by the root of the tongue or by reflex 'gagging'. This results in an enlargement of the throat's digestive portion at the expense of its respiratory portion. In other words, it enlarges the food channel at the expense of the air channel. The air channel becomes partially or completely obstructed, depending on the degree to which the soft palate is elevated. For swallowing, this elevation or, as it is commonly called, dorsal displacement of the soft palate (DDSP) is perfectly normal and acceptable.

Why does a bit interfere with striding?

At fast exercise, a horse takes one stride for each breath. Striding and breathing are coordinated so that they occur in synchrony. Anything that interferes with breathing (such as a bit) must, therefore, interfere with striding. The bit, to a degree that varies with the individual, results in a loss of that grace and rhythm of movement that is so characteristic of a horse at liberty. The constraint of movement is expressed in a more stilted gait and a shorter (therefore slower) stride.

Is it safe to ride a horse without a bit in its mouth?

Bitless methods of communication are historically older than bitted methods. Nevertheless, the majority of horsemen today are more familiar with the bit method than any other. The result is that ingrained in the thinking of most riders and drivers is the idea that a bit is necessary for control. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth. Nevertheless, it is understandable that many are nervous about dispensing with such a familiar and traditional method.

In this image which horse would you rather be ?

The riding or driving of a horse is an inherently high-risk activity and is so recognized by the laws of most states in the USA. If one engages in equitation, one has to accept that risk is involved and that there is no such thing as a guaranty of safety. So a more appropriate question to ask would be, "What steps can a rider take to decrease the likelihood of accidents?"

Will The Bitless Bridle enable me, a dressage rider, to achieve the necessary degree of poll flexion with my horse?

Yes,

The Bitless Bridle will provide all the poll flexion you require. But

perhaps this should be phrase differently. The point is that if you

wish to achieve true collection, which includes but is not limited to

poll flexion, you should strive to do this through seat and legs,

rather than by means of your hands.

Yes,

The Bitless Bridle will provide all the poll flexion you require. But

perhaps this should be phrase differently. The point is that if you

wish to achieve true collection, which includes but is not limited to

poll flexion, you should strive to do this through seat and legs,

rather than by means of your hands.

By degrees, with the emphasis on seat and legs, your horse will develop the necessary strengthening of its back and abdominal muscles so that it will gradually become fit enough to carry the weight of the rider and adjust its own balance. This is what is defined as 'self-carriage,' which can only come from athletic fitness, hind-end impulsion and a roundness of the spine.

Appropriate poll flexion is part of this roundness but not its cause. False collection, limited to poll flexion only and achieved simply by rein pressure alone, is not true collection. Sadly, because the bit is painful, it is rather easy to achieve false collection by hand aids.

Furthermore, with a bit in a horse's mouth, I would have to disagree that it is possible to be selective about which part of the mouth anatomy even the most skillful rider is stimulating. The bit is too crude an instrument to permit such finesse.

Furthermore, the assumption makes no allowance for the many different reactions and responses of your horse. The gentlest squeeze of the finger can put pressure on bone, tongue and skin. It is not possible to signal one without the others. The hope that a gentle squeeze of the fingers is transmitted only to the corners of the lips and not to the rest of the mouth is a myth and not based on reality. Similarly, if the horse chooses to retract its tongue, relatively more pressure will be placed on the bars of the mouth.

Ask your self the question:

system reflexes, so also does a bit. A bit signals a horse to "think eat". Yet a horse at exercise needs to "think exercise". The bit stimulates digestive system responses, whereas exercise requires respiratory, cardio-vascular and musculo-skeletal system responses. Eating and exercising are two incompatible and mutually exclusive activities. Horses have not evolved, anymore than we have, to eat and exercise simultaneously.

Diagram A: Below

Normal configuration of the throat for bitless horse

whilst running.

Note: The soft palate is 'vacuum packed' and stable in its normal position. There is an airtight seal at the lips and between the two parts of the throat allowing air to freely pass into the lungs.

Diagram B: Below

Abnormal configuration of the throat when running in a bitted bridle. The bit (yellow dot) has broken the lip seal, allowing air to enter the oral part of the throat.

The soft palate (flap) is UNSTABLE and is shown in

an elevated position that is ONLY APPROPRIATE to a phase of swallowing.

THE AIRWAY IS SEVERELY OBSTRUCTED at the junction of the nasal cavity and the throat (red dots)

For the purpose of eating, the horse responds with an open mouth, reflex salivation, and movement of the lips, tongue and jaw. All these responses are stimulated by the presence of a bit. When a bit is in place, for example, retraction of the tip of the tongue tends to occur.

If you place a pencil in your own mouth, you instinctively explore it constantly with the tip of your tongue. The horse does the same with a bit and, consequently, the root of the tongue often bulges upward and moves the soft palate in the same direction.

The throat, which is capable of serving either swallowing or deep respiration (one or the other but not both at the same time) is, by the presence a bit, programmed for swallowing. Accordingly the tongue tends to be mobile and so also is the soft palate which lies on the root of the tongue.

From time to time during exercise, the soft palate will tend to be pushed up by the root of the tongue or by reflex 'gagging'. This results in an enlargement of the throat's digestive portion at the expense of its respiratory portion. In other words, it enlarges the food channel at the expense of the air channel. The air channel becomes partially or completely obstructed, depending on the degree to which the soft palate is elevated. For swallowing, this elevation or, as it is commonly called, dorsal displacement of the soft palate (DDSP) is perfectly normal and acceptable.

For

the purpose of exercise, the horse needs a closed mouth (the

horse is an obligate nose-breather), a dry mouth (contrary to

traditional thinking), and little or no tongue movement. The throat

should be programmed for deep breathing, not swallowing. Accordingly,

the tongue should not be on the move and the tip of the tongue should

not be retracted. The soft palate should be immobile and lowered, to

enlarge the respiratory portion of the throat at the expense of its

digestive portion, i.e. to enlarge the air channel at the expense of

the food channel. DDSP is normal for swallowing but abnormal and, in

fact, disastrous for deep breathing.

Predictably,

episodes of DDSP are especially apparent in the racehorse,

particularly in those racehorses (the Standardbred and, increasingly,

the Thoroughbred) that race with two bits in their mouth. But DDSP

also occurs in non-racehorses.

Use of a bit sends conflicting

messages to the horse's nervous system and the confusion is

particularly evident in its effect on the horse's wind. Human

athletes could not perform well with a bunch of keys in their mouth. Why does a bit interfere with striding?

At fast exercise, a horse takes one stride for each breath. Striding and breathing are coordinated so that they occur in synchrony. Anything that interferes with breathing (such as a bit) must, therefore, interfere with striding. The bit, to a degree that varies with the individual, results in a loss of that grace and rhythm of movement that is so characteristic of a horse at liberty. The constraint of movement is expressed in a more stilted gait and a shorter (therefore slower) stride.

Is it safe to ride a horse without a bit in its mouth?

Bitless methods of communication are historically older than bitted methods. Nevertheless, the majority of horsemen today are more familiar with the bit method than any other. The result is that ingrained in the thinking of most riders and drivers is the idea that a bit is necessary for control. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth. Nevertheless, it is understandable that many are nervous about dispensing with such a familiar and traditional method.

In this image which horse would you rather be ?

The riding or driving of a horse is an inherently high-risk activity and is so recognized by the laws of most states in the USA. If one engages in equitation, one has to accept that risk is involved and that there is no such thing as a guaranty of safety. So a more appropriate question to ask would be, "What steps can a rider take to decrease the likelihood of accidents?"

Will The Bitless Bridle enable me, a dressage rider, to achieve the necessary degree of poll flexion with my horse?

Yes,

The Bitless Bridle will provide all the poll flexion you require. But

perhaps this should be phrase differently. The point is that if you

wish to achieve true collection, which includes but is not limited to

poll flexion, you should strive to do this through seat and legs,

rather than by means of your hands.

Yes,

The Bitless Bridle will provide all the poll flexion you require. But

perhaps this should be phrase differently. The point is that if you

wish to achieve true collection, which includes but is not limited to

poll flexion, you should strive to do this through seat and legs,

rather than by means of your hands. By degrees, with the emphasis on seat and legs, your horse will develop the necessary strengthening of its back and abdominal muscles so that it will gradually become fit enough to carry the weight of the rider and adjust its own balance. This is what is defined as 'self-carriage,' which can only come from athletic fitness, hind-end impulsion and a roundness of the spine.

Appropriate poll flexion is part of this roundness but not its cause. False collection, limited to poll flexion only and achieved simply by rein pressure alone, is not true collection. Sadly, because the bit is painful, it is rather easy to achieve false collection by hand aids.

Furthermore, with a bit in a horse's mouth, I would have to disagree that it is possible to be selective about which part of the mouth anatomy even the most skillful rider is stimulating. The bit is too crude an instrument to permit such finesse.

Furthermore, the assumption makes no allowance for the many different reactions and responses of your horse. The gentlest squeeze of the finger can put pressure on bone, tongue and skin. It is not possible to signal one without the others. The hope that a gentle squeeze of the fingers is transmitted only to the corners of the lips and not to the rest of the mouth is a myth and not based on reality. Similarly, if the horse chooses to retract its tongue, relatively more pressure will be placed on the bars of the mouth.

If

you were your horse, would you prefer to be bitless ?

For

hundreds of years horses have been depicted with their mouths open

from the force of the bit.

yet bit design, virtually remains unchanged to this day.

Antique Bit Collection

Article from

www.artofnaturaldressage.com

Antique Bit Collection

For the tongue to operate naturally, notice when you want to swallow your jaw rises up from a resting position. Your tongue then fills the soft palette, allowing you to swallow so the built up saliva can pass effortlessly down your throat.

Have you tried to swallow saliva with a lump of metal in your mouth ? Try a straw placed like a bit in your mouth some time and try and swallow. At least it will be stuck between your teeth and not resting on the tongue or bars of the mouth (depending on the type of bit) like the horse has to deal with.

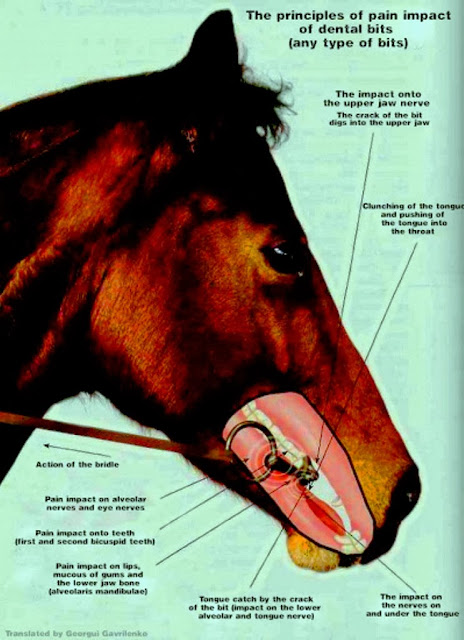

This image shows how restrictive the bit is on the tongue not allowing it to function naturally.

Article from

www.artofnaturaldressage.com

In various psychological disciplines

time and again you find that we acclimate, or accommodate, or

accustom our selves in a learning process to the paradigm.

We are told about and see a form, and at first we only related to it out of experience.

Take the form of a bitted horse in an FEI test. They all do look rather the same after all.

That horse is responding to the presence of the bit, it's activity, and it's pressure when applied. His whole body and all it's visible parts (visible to us) present a pattern to our eye.

We see it again and again, especially if we are devoted to this sport.

In time that IS the correct form, or pattern we look for in the next horse doing "dressage." If it is not there, and it won't be with using a horse that is bitless and trained bittless, we declare this horse is not performing "correct," dressage.

This same problem exists between two bitted factions in dressage, classical and modern.

Yet no one sees that both are correct for their own sport.

That is what must happen for the unbitted horse. Just as classical and modern have had to remain apart in tests or judging, so too much bittless. He must be judged on his merits as a horse that is moving without steel in his mouth.

The bitted folks make the claim that "he's not engaged," yet we who have the bittless model observed enough to recognize what is happening can see the engagement plainly. We just don't have the huge bulging muscles at the junction near the salivary glands, and so too we don't have the saliva discharge ... both are bitted paradigm elements. I would, by my view of a bitless dressage horse, a correct one, fault the rider for those bulging muscles and foamy mouth.

The rider is using the caveson too harshly and trying to escape it by getting "behind," the caveson.

The problem, Volker, is the same one present in racial and ethnic prejudice ... we fault the unfamiliar and declare the familiar to be "good," and the only true model. It is a normal human, and other animal, characteristic that once served us, evolutionarily, to survive. One must be wary of the unfamiliar and unknown.

Thus we feel comfort and "rightness," in the presence of what we know well, and rejecting and even frightened of that we do not.

Some folks resist thinking about this .. but then some resist real thinking altogether if it requires thinking about the unfamiliar.

We are told about and see a form, and at first we only related to it out of experience.

Take the form of a bitted horse in an FEI test. They all do look rather the same after all.

That horse is responding to the presence of the bit, it's activity, and it's pressure when applied. His whole body and all it's visible parts (visible to us) present a pattern to our eye.

We see it again and again, especially if we are devoted to this sport.

In time that IS the correct form, or pattern we look for in the next horse doing "dressage." If it is not there, and it won't be with using a horse that is bitless and trained bittless, we declare this horse is not performing "correct," dressage.

This same problem exists between two bitted factions in dressage, classical and modern.

Yet no one sees that both are correct for their own sport.

That is what must happen for the unbitted horse. Just as classical and modern have had to remain apart in tests or judging, so too much bittless. He must be judged on his merits as a horse that is moving without steel in his mouth.

The bitted folks make the claim that "he's not engaged," yet we who have the bittless model observed enough to recognize what is happening can see the engagement plainly. We just don't have the huge bulging muscles at the junction near the salivary glands, and so too we don't have the saliva discharge ... both are bitted paradigm elements. I would, by my view of a bitless dressage horse, a correct one, fault the rider for those bulging muscles and foamy mouth.

The rider is using the caveson too harshly and trying to escape it by getting "behind," the caveson.

The problem, Volker, is the same one present in racial and ethnic prejudice ... we fault the unfamiliar and declare the familiar to be "good," and the only true model. It is a normal human, and other animal, characteristic that once served us, evolutionarily, to survive. One must be wary of the unfamiliar and unknown.

Thus we feel comfort and "rightness," in the presence of what we know well, and rejecting and even frightened of that we do not.

Some folks resist thinking about this .. but then some resist real thinking altogether if it requires thinking about the unfamiliar.